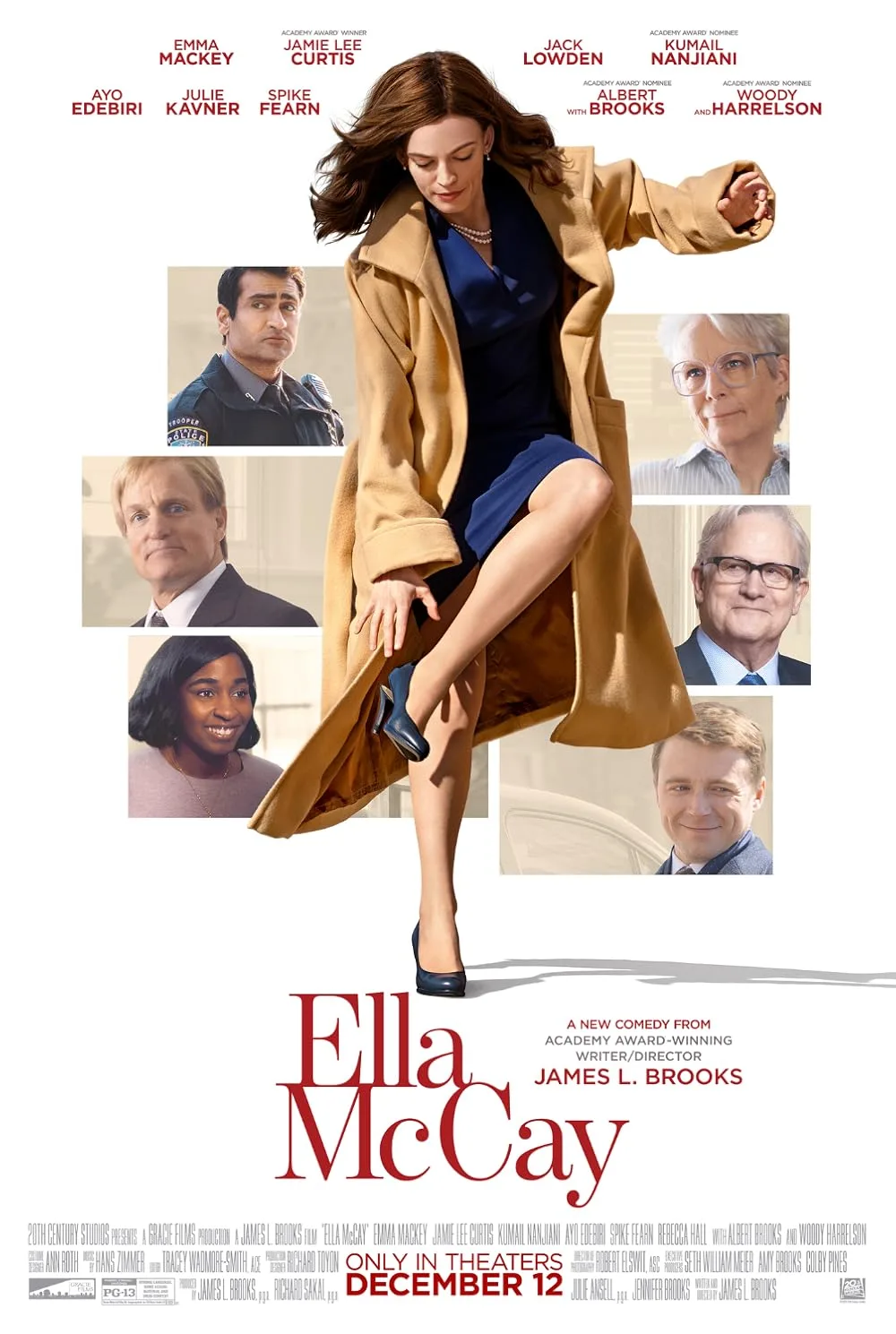

Writer/director James L. Brooks loves stories about complicated women with messy lives. His characters are more successful in their professions than in their romantic choices, but they talk about their mistakes in the kind of sharp, witty dialogue that most filmmakers have forgotten how to write. The latest from the man behind “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “Broadcast News,” “Terms of Endearment,” and “As Good as it Gets” is “Ella McCay,” about an idealistic young politician whose impulse to try to fix everything comes from her un-fixable family.

Brooks sets the film in 2008, which frees the story from today’s increasingly angry political divisions but therefore makes it come across as quaint, simplistic, and sometimes downright musty. It feels closer in time to “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” than to the politics and culture of this century. Like its heroine, it is messy. And like its heroine, its strengths make up for a lot of messiness.

In 2008, Ella (Emma Mackey) is the 34-year-old lieutenant governor of New York. Her political mentor is Bill (Albert Brooks), the governor who is about to leave to join the President’s cabinet. This means that Ella is about to become the 34-year-old governor of a state with nearly 20 million people. As he leaves, Bill tells her, not unkindly, that succeeding to the vacancy is the only way she could possibly be in that job. We gather that Bill thinks she is too honest, too direct, and too uncompromising to win an election. Those qualities may not persuade voters, but she has the devoted loyalty of her outspoken Aunt Helen (Jamie Lee Curtis, still living her best life with a series of performances that expand her range), her sympathetic administrative assistant Estelle (Julie Kavner), and her driver/security detail, Trooper Nash (Kumail Nanjiani, underused).

In a flashback, we see Ella as a high school senior, trying very hard to be perfect and to create a perfect family for her mother (Rebecca Hall) and much younger brother, Casey. The problem is her feckless father, Eddie (Woody Harrelson), who has been fired for having many relationships with women on his staff. When the family has to move so her father can start over, Ella stays with Aunt Helen. After their mother’s death, Casey goes to a military boarding school. And Ella, perhaps trying to create the family she wishes she had, marries her high school boyfriend, Ryan (Jack Lowden). He is a friendly, outgoing guy who works at his family’s chain of pizza restaurants. Back in 2008, as the press crowd around Ella following the announcement of Bill’s departure, Ryan races up to hug her. Is he genuinely proud of her and eager to show his support? Or is he hoping her new job will help him gain attention and power?

Ella is sworn in as governor and immediately faces crises in both politics and family. Ella’s minor infractions involving the use of state property are suddenly fuel for political opponents to exploit. And after many years of no contact, her father shows up, not because he has any genuine feelings of regret or accountability, but because he has a new girlfriend who says she will not stay with him unless he reconciles with Ella and Casey.

Ella’s primary concern is protecting her brother (a terrific performance by Spike Fearn). Casey is brilliant but vulnerable and reclusive. He insists he is not afraid to leave his apartment; he just chooses not to.

Both siblings are overthinkers. Ella is constantly trying to solve a dozen problems at once. Casey struggles with anxiety and is still obsessing about coming on too strong a year earlier with the girl he likes (Ayo Edibiri as Susan). Some of the film’s best scenes show the tenderness Ella and Casey share, respecting each other’s differences and limits, including her need to fix everything and his need not to be fixed. “I’ve decided not to be normal. Pick something easier,” he tells her. Ella encourages him to reach out to Susan, and Casey leaves his apartment to try. Edibiri makes Susan confused but captivatingly warm and open. In a small part, she does a lot to make the point that you don’t have to fit some narrow idea of normal to be seen and loved.

The personal stories work better than the political commentary, and the ending is abrupt and unearned. Like Brooks’ most recent feature film, 2010’s “How Will I Know,” this does not hold together well as a whole. It is a movie of moments. But some of those moments are so good, its optimism is so refreshing, its dialogue so bright, and its characters and performances so endearing, it well rewards a watch.