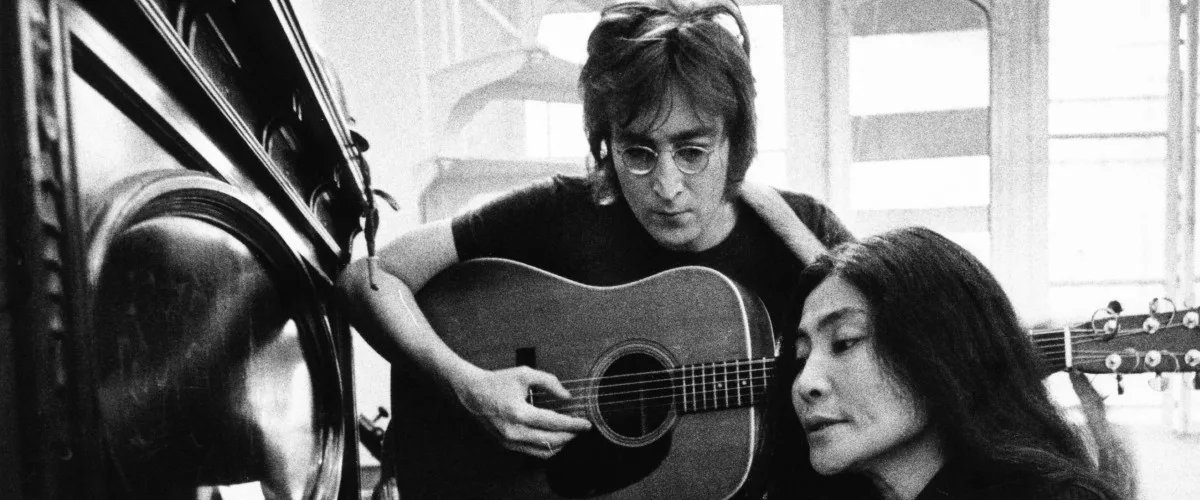

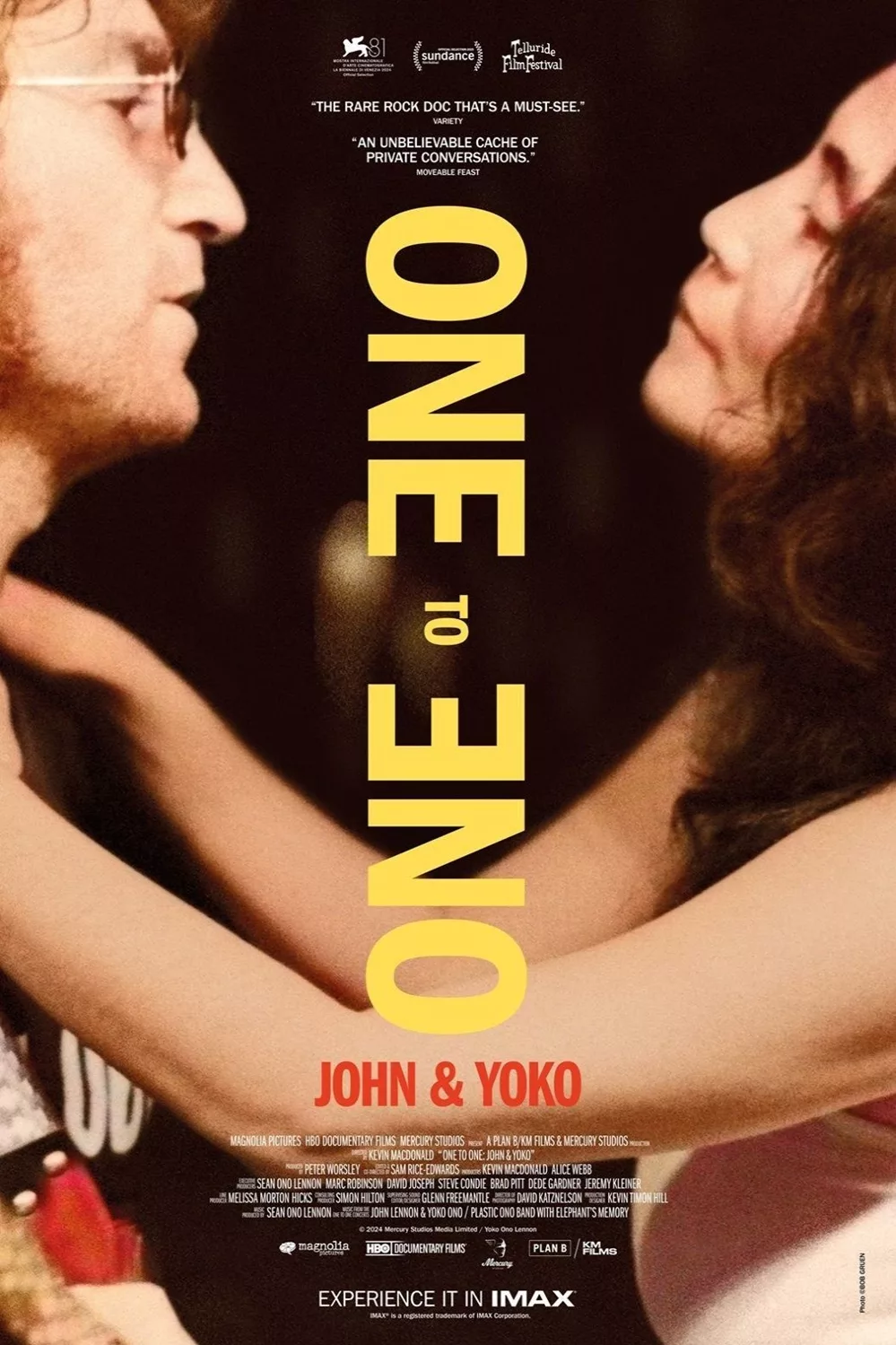

A minor irony of this often exhilarating documentary is that it partially chronicles the circumstances that led to John Lennon’s least artistically consequential album, the 1972 “Some Time In New York City,” a collection of protest tunes of forehead-smiting obviousness. (Critic Robert Christgau described its contents as “tuneless topical rock songs” and said the album was where “Lennon risks his charisma instead of investing it.”) Kevin Macdonald’s film combines archival footage, concert material, and a reconstruction of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s modest loft on Greenwich Village’s Bank Street to create a compelling portrait of two famous artists sitting around watching television. Until something they saw on the television compelled them to revive their activism.

The Lennon-Onos owned a large estate in England that afforded them a lot of space and necessary privacy. However, Lennon’s radical self-examination, which began with his album “Plastic Ono Band,” also helped make him a political animal. Hence, a need to live among “the people” and in a city that energized him, New York. Once ensconced on Bank Street, he roosted there with Yoko. Their reel-to-reel tape recorded took down their phone calls. Lennon insists, in a recorded quote, that the tube was a legitimate mirror into what was going on in the world. He wasn’t wrong. And after a time, he decided to use the medium rather than just watch it.

He got himself and Ono onto the popular afternoon chat program “The Mike Douglas Show” for a week (this stint is the subject of a different standalone documentary, 2024’s “Daytime Revolution”). On that show, he reintroduced Middle America to then-radical activist Jerry Rubin, who had been one of the Chicago Seven. So besotted was Lennon with Rubin that he concocted an entire tour around a double bill of himself with the agitator, rallying the youth all over the country and finally delivering some kind of revolutionary coup de grace at the 1972 Republican National Convention in Miami that summer.

In what was perhaps not a coincidence, the State Department began deportation hearings against Lennon, which compelled him to scramble a bit. John and Yoko weren’t in the U.S.A. merely because they liked it; Ono was trying to regain custody of her daughter Kyoko, who’d been transported to the States by her father.

The movie is at its most fascinating in its depiction of Lennon as a pragmatic activist. Calling for revolution in a series of concerts not being the most prudent course of action, he is subsequently moved by television journalist Geraldo Rivera’s harrowing 1972 account of the awful conditions at Staten Island’s Willowbrook State School for children with mental disabilities. The neglect suffered by these children underscored the thing they required and weren’t getting: One-to-one treatment. Here was something Lennon could put together: a concert to raise money for these kids.

And so he did. Others throwing in their talents were the retro band Sha-Na-Na and the legendary Stevie Wonder. But the concert footage here is all of Lennon, performing one of the only two concerts he gave as a solo artist. More’s the pity — it is no surprise that he’s a great performer. The afternoon before the show, some Willowbrook kids were bused out to Central Park for some time in the sunshine, and this too is very moving. True, activist songs like “John Sinclair,” about the Detroit activist who got sentenced to ten years in jail for possession of two joints, weren’t Lennon at his most advanced or inspired: “It ain’t fair/John Sinclair/in the stir for breathin’ air.” But maybe they got some job done; there’s also footage here of a grateful Sinclair hugging Lennon as he’s stepping out of a jail cell. Impressive.