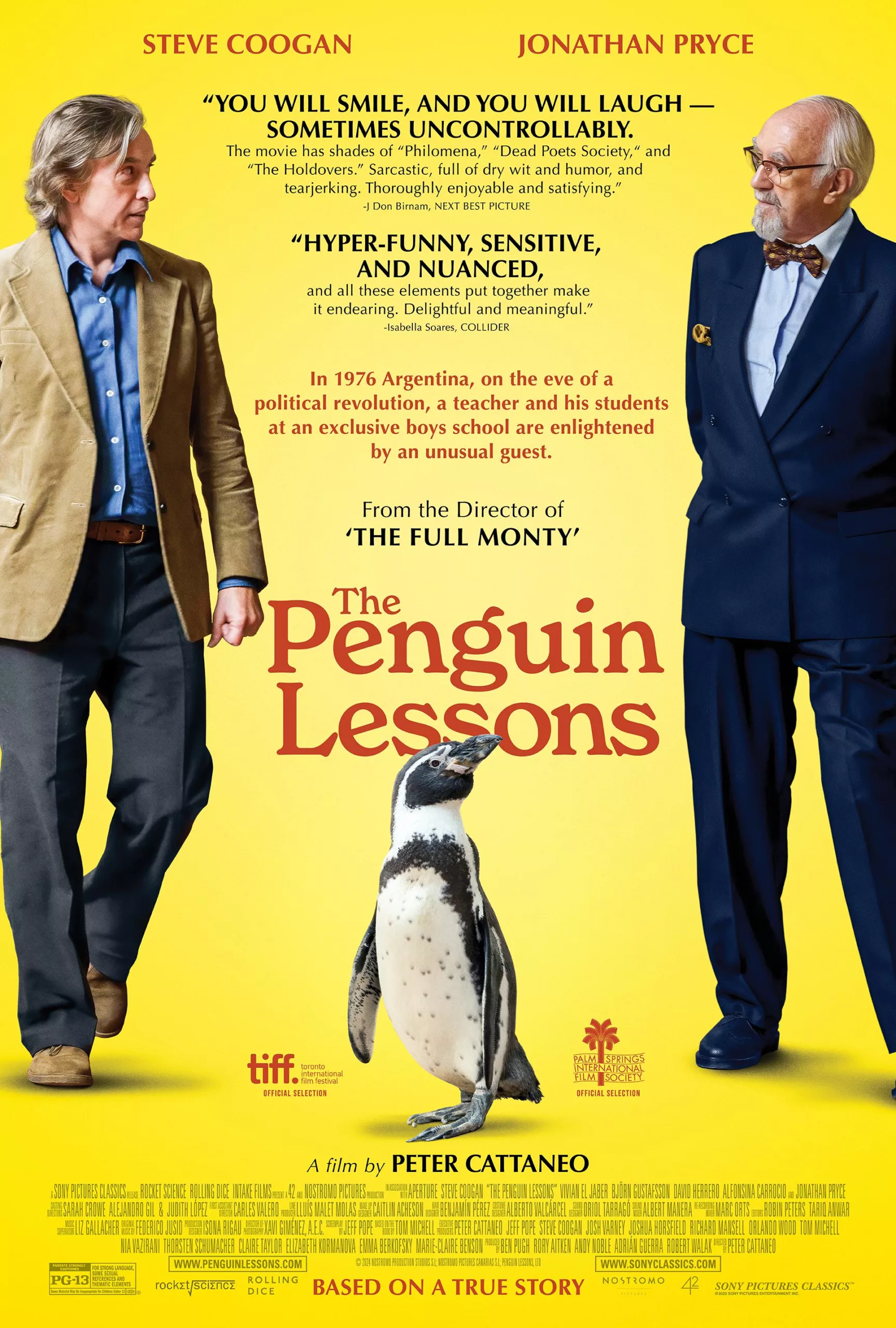

“The Penguin Lessons” is a throwback to roughly thirty years ago, when small-scale, heartwarming comedies about plucky outsiders made tons of money for art house theaters. It’s even directed by Peter Cattaneo, whose comedy about amateur male strippers ‘The Full Monty” was such a hit that it spun off a Broadway musical. There won’t be a Broadway musical based on “The Penguin Lessons,” unless a real life version of one of the tap-dancing penguins from the “Happy Feet” movies is willing to move to New York—and that’s for the best. Based on a 2016 memoir by Tom Michell, “The Penguin Lessons” wants to be a thoughtful light entertainment about ideals and courage, but ends up seeming grotesquely misguided.

It’s about a mopey, mentally checked-out teacher named Michell (Steve Coogan) at a boys’ private school in Buenos Aires, Argentina, who evolves as a person in response to a right-wing military dictatorship taking over the country. Imagine “Dead Poets Society” with secret police. Depending on the country you live in (including the United States, as of 2024), that might not be much of a stretch.

But that’s not what this movie is actually about. It’s a softhearted, softheaded work that piles a lot of overly familiar elements into a single film, including “bloody upheaval in developing country as experienced by a privileged white foreigner who’s isolated from the worst of it”; “detached cynic has moral awakening” and “sad, unpleasant guy becomes nicer after taking care of someone, or something.”

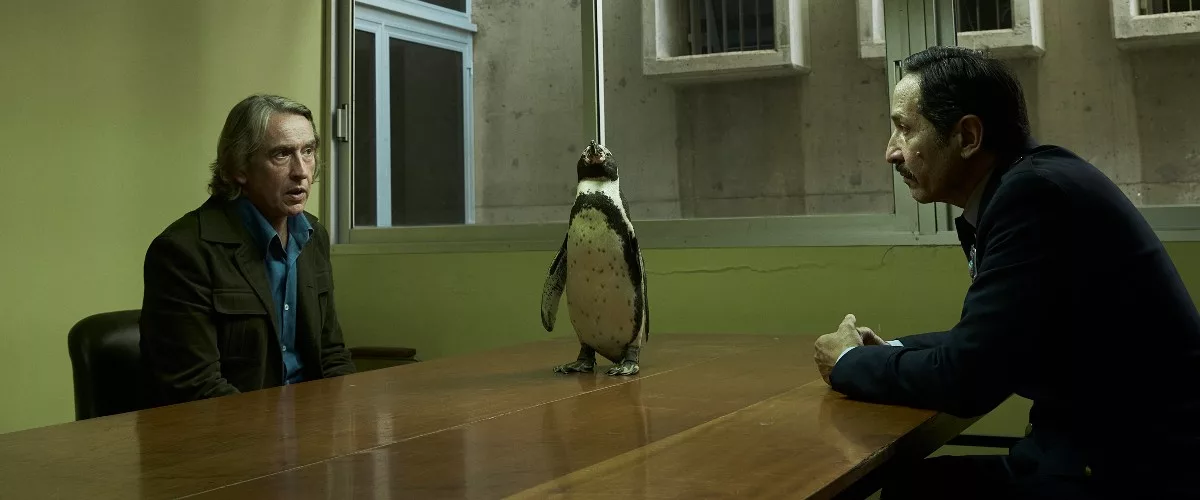

The latter is an emperor penguin that Michell, a teacher at St. Georges’ College in the suburb of Quilmes, encounters while trying to get laid on vacation at a Venezuelan resort. The bird attaches itself to Michell and becomes a combination pet, foundling child, and malleable metaphor. A staffer at the school dubs him Juan Salvador. Michell lets him stay in his flat even though he stinks and keeps pooping on the floor. Sometimes, Michell smuggles Juan Salvador to other locations in an oversized tote bag. There are scenes where Michell thinks he’s gotten away with hiding the penguin only to have it squawk and alert everyone. It’s a can’t-miss bit, so of course, the movie keeps doing it.

There’s also a subplot about a friend of Michell’s who is involved in an underground movement to resist the military takeover of Argentina and suffers for it (apparently this is not in the book). To avoid specifics, let’s say the government skullduggery gets Michell directly involved in Argentinean life and challenges him to get over a past trauma and stand up for the people he cares about. This is useful, plot-wise. But it creates a tonal schism between the first and second halves of the movie that’s too vast to be bridged.

The first half-hour could’ve been the opening section of a Bill Murray or Robin Williams or Adam Sandler comedy about a sullen reprobate who lightens up and redeems himself. That’s fine as far as it goes. But it’s hard to fuse that kind of template with the so-called Dirty War, which lasted from 1976-83. Enemies of the ruling government were snatched off the street without warning, leaving a ghastly question mark in their families’ lives. Designated enemies of the regime were murdered, tortured, disfigured, raped, subjected to unnecessary surgery, and held in subhuman conditions for years on end. For more about this era, watch any one of the many thoughtful dramatic films about the Dirty War, including the 2021 drama “Azor.” Just don’t expect penguins.

There have been other comedies set against the backdrop of authoritarian and/or genocidal historical movements, including Nazi Germany’s (notably “Life is Beautiful” and “Jojo Rabbit“), that detractors wrote off as tasteless and insensitive because of their premise. Whether or not you agree with such assessments, it can at least be said that those movies deal (however glancingly) with the tragedies unfolding around the characters; think of the scene in “Life is Beautiful” where the hero, a concentration camp inmate, stumbles upon a hill made of prisoners’ corpses. Other comedies about authoritarianism have rubbed the audience’s nose in awfulness until discomfort morphed into cathartic laughter at how rotten people can be. The best recent example is “The Death of Stalin,” a satire with a coal-black heart.

In comparison, “The Penguin Lessons” is a limp, safe, calculating movie. It puts the Dirty War in service of helping a detached foreigner understand the meaning of courage, and builds to a string of happy endings that feel unearned. One supposes we’re meant to leave the movie feeling hopeful about humanity because we’ve seen one man make a difference. But then comes a title card telling us 30,000 people were killed or disappeared in the Dirty War. What are we supposed to take away from the movie? That it’s a shame all those people are gone, but at least a visiting Englishman became a better person and learned to love again?

There is a central tragedy that the film does feel deeply, but it’s not one that connects with the larger story. I think you know what I’m getting at.

There are wonderful performances in “The Penguin Lessons,” notably by Coogan as the conflicted hero; Jonathan Pryce as the school’s headmaster, who warns him not to make waves; Lars Björn Gustafsson as Coogan’s earnest young colleague, a science teacher who seems more straitlaced than he really is; and an array of superb Argentinean actors, including Vivian El Jaber and Alfonsina Carrocio as members of the school’s maintenance staff who are closer to ground-level of the country’s upheaval.

There are also restrained but potent sequences showing what happens when a state’s monopoly on violence is used as a blunt instrument to settle ideological scores, as well as some lighter bits that show what authoritarianism does to a nation’s economy (the school’s bursar advises Michell to spend each week’s paycheck on consumer goods and resell them quickly because the currency gets less valuable by the day). The filmmakers do a creditable job of cutting together shots of the human cast and closeups of the penguin turning its head or squawking (likely in reaction to someone waving a fish off-camera) so that the bird appears to be interacting with humans.

But overall, “The Penguin Lessons” is a study in avoidance. It would rather be liked than good.